Wattle and daub houses of Mision Tilaco, Sierra Gorda

May 2019, Tilaco, Queretaro, Mexico

In May 2019, me and my students went on a study trip to Tilaco, fampurs for its special type of wattle and daub houses.

Based on the the surveys of the ministry of tourism, only three distinct structures in totality of bajareque remain in the town of Tialco. The representative from the ministry of tourism, Tilaco secured permissions for personal interviews with the owner – builders of the houses.

A group of architects from queretaro, participated in the survey, measured drawing, use of photographic evidence to document the existing structures. Personal interviews with the owner-builders were used to clarify observations and to gain an insight towards the following objectives.

- To understand the materials, components and the constructive systems of the use of mud and fibre, in the town of tilaco.

- To understand the origin, history and use of the structures that remain in the town of tilaco.

- To understand the changes in use and the corresponding evolution of the structure and its components.

- To understand the kind and amount of timely maintenance that was needed through its lifetime.

- To understand the current state of use, the present condition and the preservation efforts that will be needed to preserve these structures.

There has been little maintenance, mainly because the house used to be the responsibility of the whole family. The Sons and daughters have long left tilaco, and the house has been left in the hands of the eldest daughter. Since the day the parents died, there has been little changes to the houses. The main reason is the lack of consensus on what to do with the family home. There is little incentive to preserve the building for one person, as they already have modern buildings on the same plot and the vernacular structure is no more than a vestige, not being used for anything other than the occasional storage of maize after harvest. Most of the maize is now sold after harvest as they say that the maize nowadays does not store well for the year. The house stays empty most of the year.

The family now does not even grow maize, but rather buys it. They are not growing anymore as the children are not interested. Nor is the land being as productive. Special seeds of “cebada” and “trigo” are being used now.

The main beam of the house, they say suffered an internal damage, thanks to Polilla and the roof has been rendered structurally unstable since. The beam has clearly cracked but it is still holding up, thanks to the diagonal members and the stability of the rest of the wooden members of the roof.

It is clear that the maintenance is not an investment of money but of time. Because it needs collective time, there is rarely a time when all come together to get a consensus. Leave alone time to fix the house. The eldest daughter now talks about demolishing the existing house, as it has just been occupying space and not serving any purpose. Even for demolition, a family consensus has not been achieved so far. Only that explains the existence of the house today.

The older house ( house of the parents) was demolished, when the other children moved out and the eldest daughter built a modern structure with her husband (with money obtained from his occasional work in the United states.

During demolition, they say that they could not rescue any wood. They saw that the wood of the demolished house was already black and rotting. Also the wood was structurally weak due to Polilla de madera o Cárcoma.

Bathrooms and the lifestyle, 30 years ago. There were no toilets, and everyone in the house went out to the then “huizache” or the “cerro” for the daily duties. The space/area between the houses of bajareque were used as areas for taking a bath.

They occupied about 40l per family of 4. Two “botes” were filled with water down at the village wells (found in the valley) and were brought up carrying on their heads.

There were no schools and hence there was sufficient time at hand with the kids of the family. Mainly water was brought up by the

Maize used to be grown previously, but nowadays there is little labor available in the town. Most grandparents have smaller holdings where the bare minimum is cultivated.

The construction of Barroteo and enjarre en Tilaco presents some very distinctive features as compared to the other examples of bajareque seen in Mexico.

Here is a sequence of construction as explained by the builders of the third house.

Excavation

Pits a dug in the location where the horcones are to be placed. The largest horcones are placed in the corners, they are placed over a stone with a wider base placed flat into the dug pits. The pits are then filled with large flat stones to stabilize the horcones. There is no excavation done in the interior of the house neither is the floor raised.

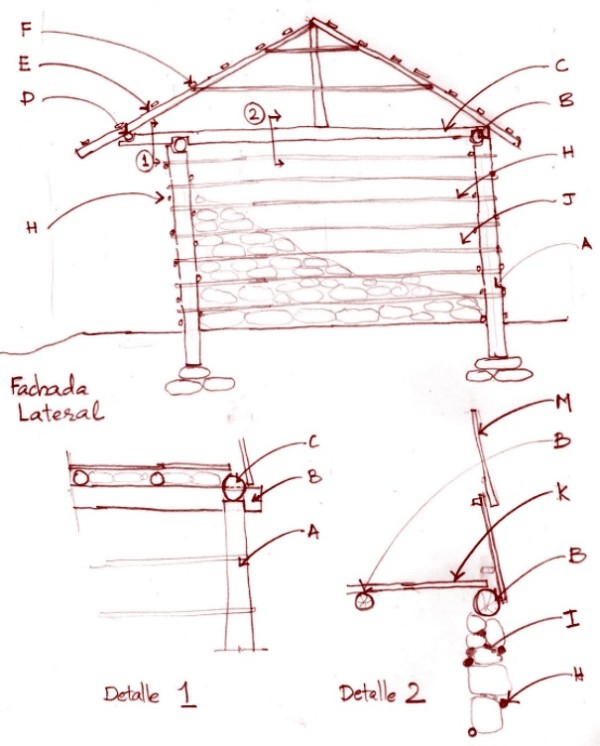

A – Horcones

Interior horcones are then placed in new pits, one for each door / window. Typically the houses have one door and a window. Some have more than one, while the doors / windows are never opposite to each other. This way the interior horcones do not align to each other laterally, but only longitudinally between the corner posts. The heads of the horcones are cut to recieve the Solera. The arrangement of the posts / horcones can be seen in figure 1.

B – Solera

Soleras are placed longitudinally, from corner to corner. They do not extend beyond the horcones. It was said that previously they were tied in place with strings of bejuco de gallenam, as of today, the bejuco is not visible. Simple joinery with the vigas limits the movement of the soleras. Soleras are sometimes two overlapping round logs, with the thicker ends at the corners and the overlap at the centre.

The Soleras and the horcones are both of Cedro Blanco and have no treatment / finish. The bark is peeled off and left to dry before use in the structure. The soleras and the roof above is simply placed over the horcones and hence can be moved / taken off.

The soleras function as the base support of the roof structure and at the same time prevent the horcones from moving longitudinally.

The two soleras are tied together by two lateral Vigas.

C – Vigas

Are the critical structural members of the roof that act like tie beams. They are of similar diameter as that of the Soleras. They have a half cut at the point where the solera rests on the horcon and at the same time, rest on the horcones. The load is directly transferred to the horcones, however, due to this special joinery, the soleras and hence the horcones are stabilized laterally. In the interior, vigas cross the space and are resting on the soleras about 70-80 cms centered. They limit the movement of the soleras, and at the same time tie the two longitudinal walls and horcones. On the southern side, the Viga is thicker and has a rough cut – joinery to receive and provide support to the Sobre solera. The vigas, thinner end extend about 30-40 cms on the nothern / eastern facade and do not recieve a sobre-solera on this end.

The vigas also form the structure for the tapanco on the interior.

The placement of the vigas do no correspond / align to the interior horcones.

The space between vigas, above the solera, is filled in with selected flat stones of similar thickness to fill the gap and at the same time limit the movement of the vigas along the longitudinal axis of the structure.

D – Sobre Solera

The sobre solera is a thinner member on the southern / western facade, that allows the overhang. Its purpose is to support the latas, that will form the gable over the interior space. These 2” round members rest on the notch cut up in the vigas, and are nailed to the vigas.

E – Lata

The latas align with the vigas. Two latas are placed with the thicker end up to form the gable of the roof. At the ridgeline, the latas are joined by a simple notch in one of the latas thicker end. The other end rests on the sobresolera, on the southern / western side, and the solera on the northern / eastern side.

They are 3-4” in diameter and are placed at an angle of about 26 degrees slope. Due to the overhang on the south / west facade the ridge of the latas do not align with the centre of the space. This off centered alignment is typical to tilaco.

At the ends, the latas are tied together with barrotes, the barrotes are simple 2” ties running horizontally, and connecting the two latas at the end. They are 12” centred and receive either tablas, palma or function as the barroteo system itself.

The latas have diagonal bracing, arising from the internal vigas to limit its longitudinal movement. The lateral movement is limited thanks to the sobre solera and the soleras.

The Latas, receive the Cintas that will finally support the roof membrane.

F – Cinta

The cintas are 2” rectangular members that run longitudinally. they were initially tied to the latas using bejuco. The structures that exist today in Tilaco, have the Cintas nailed to the latas.

The cintas finally recieve the roofing. Three distinct types of roofing are seen in tilaco.

- The use of Palma, overlapping is a local art that is long lost. Most are aware that the method exisits but the skill to execute a palma roof is not easily available. The previous generation was the last to have used this system. Palmas do not last long, but can be easily replaced as it is widely available in the region.

- The use of tablas / tejamanil, is still visible in most traditional roofs. These tablas are about 1-2 cms thick, 8-10 cms wide and and 48 -50 cms long.

- The use of Corrugated zinc coated iron sheets.

G – Puerta y ventana

The door is a simple assembly of boards that are placed edge to edge, but nailed to a frame of “barrotes” that would close in to a frame. The frame of the door also acted as a structural “horcon” and carried the weight of the roof. They had the same structural integrity, size and characteristics of the corner horcones.

Doors and Windows were locally made by the carpenter, the wood is procured from the forest, from the terrenos ejidales with permission from the community.

H – Barroteo

Finally after the roof, dor and window is in place, the barroteo is done, where first thin long branches / varras of a local plant called Zihuapantle is placed, the bark is not removed nor is there any treatment done. The thicker ends of the varras are placed at the corner Orcones and the tinner ends stop at the door frame / inner horcon.

First two varras are fixed to the horcones at the base, normally over a arrangement of larger flat stones. These large stones seem to help in limiting the rize of humidity from the gound. There is little mortar visible at the base between the foundation stones.

The barrotes in the cross section are laid in a diagonal manner, first filling the space with rocks and mud.

The mud is a white clayey – sandy mixture, obtained from the lower slopes of the valley of Tilaco. Slowly the barrotes are tied / nailed while filling up the wall with the Enjarre

I – Enjarre – de Varras y piedras – build together slowly. Tierra y piedra con agua. The rocks seem to rest on the varras, the first one resting on the exterior and the second layer resting on the interior varra. The space between the varras and the piedras is filled with the enjarre.

J Aplanado de tierra : In all theree houses there is a limited use of a aplanado / fine plaster on the interior. A few houses however have finished the interior with a modern cement / lime sand plaster, left unpainted.

K – Tapanco

Tapanco – de madera de otate, similar a bamboo, finger like, but is solid.

L – Floor

The interior of the floor used to be of mud they say. The mud floor that they talked about was not found anywhere. All foors were of concrete laid rough and level without much fuss for a clean finish.

M – Walls under the gables

Zibabantle – The roofs were all of wood previously, of Cedro / cedar. But over time, when the use of tin sheets came, they laid the sheets over the wood simply nailing them down.

Cedar (cedro) – The beams and the columns, soleras y contra soleras

Form and orientation

- The Size of the unit, 3.5m x 5.5m was quite constant in all the three examples found in Tilaco, with little variation (30 cms). This apparent standardization of unit size and the reasons for the same are unknown.

- The orientation of the house does not seem to be important, as the houses were found to follow the contours of the site. The main doors opened up to the principal patio or towards the garden / Milpa.

- The exterior walls of the houses were almost always adorned with hanging plants or with creepers growing on them. Commonly used tools were left hanging / nailed to the walls. There was no special space for the storage of tools. This displays a sense of security that the community still reserves.

- The Roof structure and placement of horcones, show similarities to the structures found in Ocosingo Chiapas. With a overhang on one side and the tapanco extending out to shade that side.

Atmosphere

- In all three examples, the sense of rusticness is still intact, with the lack of any plaster on the interior walls and the unfinished nature of the floor. As compared to the houses of Chiapas, or of Yucatan, where a mud / lime plaster seals the walls. The walls in Tilaco have a distinct character owing to an unforgettable identity of rusticness.

- In all there examples, the sense of darkness during the day. The doors and windows of wood can be closed to cut off all light from the exterior and are usually left closed during the day. This pattern can be observed in the vernacular examples of both chiapas and in Yucatan presented in this paper.

- In all three examples, the interiors presented a “very comfortable” indoor climate, where there was little movement of air, cutting out the sounds and smells of the outside, creating an introverted personal world. This sensation, can be partially be attributed, and felt in both the houses seen in Chiapas and in Yucatan. This phenomenological experience is reserved by the author 2 is open to critique by researchers studying indoor experiences of vernacular architecture of bajareque in Mexico.

- The kitchen was always found in the interior of the spaces, and the soot found to be further darkening the walls on the inside in all three examples. However, in Chiapas, the cooking was done outside, on a backyard. The location of the kitchen and the fire is not studied in the example of the houses found in the Yucatan.

Construction

- The barroteo us clearly distinct with thicker, nonuniform varras used from Horcon to Horcon, covering the longest stretch possible.

- There is no weaving of the barrotes, ie. the barroteo is clearly on one side of the wall, thus forming a external structure (armature) holding the infill and keeping it plumb. The barroteo only acts as a support for horizontal movements / forces.

- The barroteo does not carry the load (vertically) of the infill. The infill stone appears to be load bearing on its own.

- The stone and mud filling is a thinner form of stone masonry that is built from ground up. The mortar filling in the gap formed by the irregularities of the stones.

- There is no use of a binding fiber in the mix used for the enjarre. The mud used is virgin, not mixed or modified with any type of modifier of soil. Humid natural available soil specifically selected from the valley is used as the masonry mortar.

- There is no traditional plaster over the barroteo or the enjarre. Both are left exposed to the elements, thus, it appears that the structure is quite durable, and requires lesser maintenance.

- The walls are only 15 cms thick and, present a very comfortable indoor environment throughout the year. The lack of openings for direct radiation, keeps the indoors cool during the day and controls the lack of heat during the night.

- The Wall below the gable of palmas / tablas is different from the Barroteo below it, thus exhibiting a distinct character to the houses of tilaco.

- The houses “they say” have the possibility to be moved from one place to another, or to be expanded at will. This is mainly attributed to the fact that the roof rests on Soleras (that can be lifted off the main structure of the Horcones) without dismantling the roof. The roof made of Palmas, is rather light and presents a innovative response to this necessity of moving / displacing / modifying a space as needed. Further information and research is needed to understand exactly how this is achieved.

As noted above, due to these distinctions, it is to be questioned, if this method of construction should actually be considered bajareque. Whether the origins come from traditional bajareque (of chiapas), or from attempts to make thinner, externally reinforced stone masonry (as seen the mayan house of yucatan) is unknown.

It is clear that the houses of Tilaco present a very evolved form of building, that is responding to the materials available in the valley of tilaco. However, further study is needed, of communities in Sierra Gorda of Queretaro and of Mexico in general to understand the evolution, transfer of technique, knowhow and skills.

Further research will present the much needed expertise in building, maintaining and continuing the traditions of the vernacular architecture of Tilaco. The absence of jobs, lack of human economic activity and the excessive migration of the younger generation, places the building traditions of Tilaco in the risk of extinction. These last three houses in Tilaco, need to be conserved without fail, as they are written testimonies of a almost forgotten continuity.